At Curtis High School, the promise of equal education is being quietly broken—one locked door, one broken elevator, and one inaccessible classroom at a time.

Federal laws such as Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) exist to guarantee students with disabilities equal access to education. Section 504 prohibits discrimination based on disability in any program or activity that receives federal funding—including public schools.

The ADA builds on this by requiring schools to provide reasonable accommodations and remove barriers that hinder full participation. Together, these laws require schools not only to maintain accessible facilities but also to implement active policies and procedures that support students with disabilities. Yet for students with temporary disabilities or disabilities that were acquired after enrollment at Curtis, these mandates often feel like distant ideals rather than daily realities.

Students with temporary disabilities caused by injuries are frequently expected to manage without accommodation, under the assumption that their condition will improve quickly. However, this often results in missed class time, academic setbacks, and unnecessary physical strain during recovery.

Many injured students push themselves physically and emotionally just to keep up. The problem isn’t motivation—it’s mobility. When classrooms are three or four floors up, when elevators are broken, and when contingency plans are vague or nonexistent, students are left with a painful choice: risk their safety navigating to class or miss out on their education.

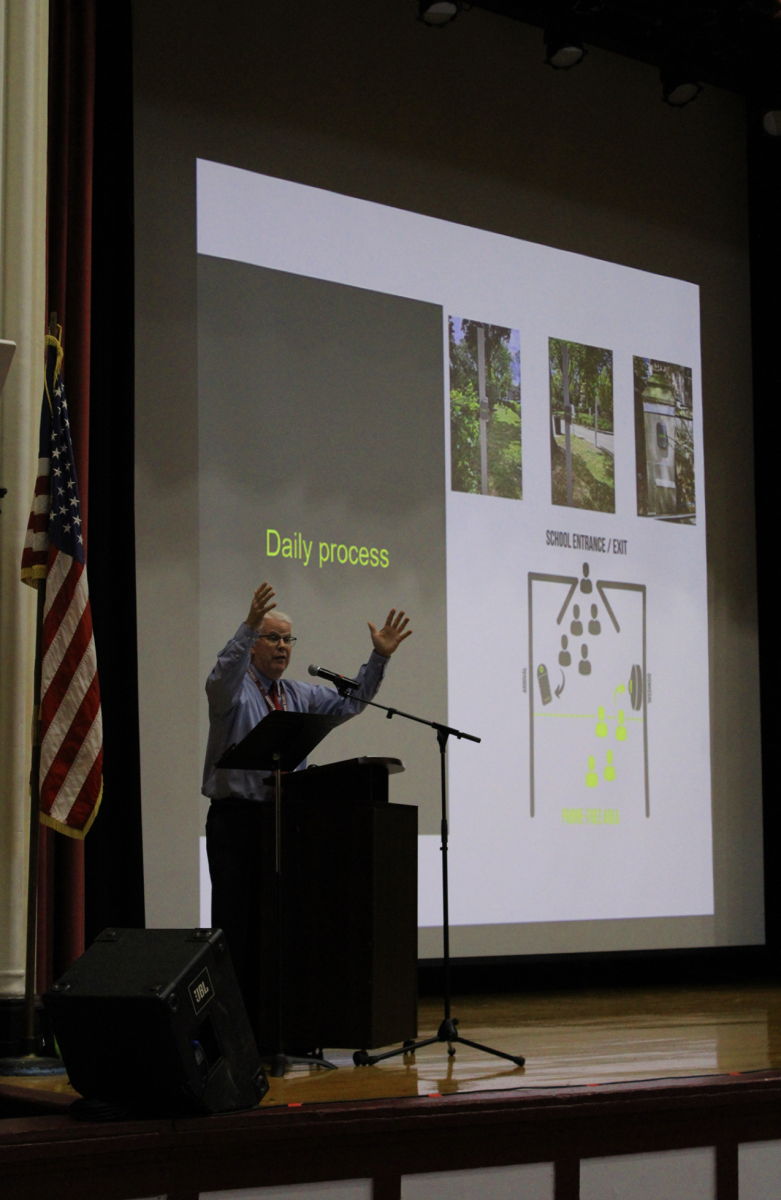

“Unfortunately, we don’t really have a mechanism for when our elevators are down. It’s an over-100-year-old building, and the elevators often need repairs. In the past, we’ve had to put students in a particular room and get them work, but I know that’s not ideal because they miss full instruction,” said Assistant Principal of Security José Burbano.

When asked if there were any specific plans in place to support students with temporary or permanent disabilities when the elevator is not working, Mr. Burbano was very candid: “No, to my knowledge, there are not. There’s no designated staff assigned to help students during transitions if the elevator isn’t working.”

Some try anyway. Limping up flights of stairs. Relying on friends to carry bags. Using hall passes longer than allowed because it takes triple

the time to get from class to class. Others are told to stay in the library or a random available room—essentially removed from their peers, their teachers, and the lessons they were scheduled to learn.

At Curtis, however, access to education often hinges less on effort and more on physical realities: whether an elevator is functioning, or whether a door is unlocked. These everyday obstacles don’t simply cause frustration—they reveal a deeper, systemic problem.

These issues are not isolated incidents but structural barriers. Curtis is a sprawling school with over 350,000 square feet and only four elevators. When even one elevator is out of service, large sections of the building become inaccessible. Certain classrooms above the lunchroom—located on the third and fourth floors—are always unreachable because no elevator services those areas. The lunchroom lacks a ramp, so it too is inaccessible.

Curtis has tried to make the school more accessible. “We’ve talked for over 10 years about installing ramps, but because the hallways are so tight, it was never approved. It’s something that’s likely beyond us—it would have to come from the DOE,” Burbano said.

One of those three elevators—the one near the auditorium in the middle building—is critical for students trying to access the new building. When that elevator is out of order, students in need of mobility support are forced to abandon their schedules entirely or rely on uncertain, makeshift plans. And “contingency plans,” when they do exist, often lack clarity, communication, and compassion.

Maya Scheffler, a senior at Curtis, experienced this firsthand. After a ankle injury left her temporarily disabled, she expected the school to have a plan to help her navigate. Instead, she was met with confusion and silence. “It felt like I was being punished for being hurt,” she said. “I didn’t ever have a consistent plan.”

I know what Maya means, because I went through it too. After a devastating knee injury to both knees, I had to rely on the elevator to get to class. One day, it was broken again, and there was no plan, no backup, no one there to help. I stood there, stuck – until a friend showed up and helped me down the stairs, step by step. We were both nervous the whole time: what if we fell? What if we weren’t allowed to do this? What if I just couldn’t get there?

No student should have to risk their safety in order to attend class. No one should have to choose between staying safe and staying on track academically. And yet, that’s exactly what’s happening.

One of the biggest fears is what will happen in the event of an emergency, how will students with mobility challenges be safely evacuated or relocated. Mr Burbano stated, “We do have emergency ‘safe rooms’—two on each floor—equipped with staff to supervise these students. In an emergency, first responders are trained to check those rooms. It’s written into our official safety plan.”

The Department of Education mandates that schools must have functioning accessibility plans in place—not just on paper, but in practice. That includes physical access to classrooms and lunchrooms, clear contingency protocols, and a learning environment that doesn’t penalize students for injuries or disabilities. The school’s age cannot be used as an excuse to avoid accountability. Both the DOE and Curtis need to work together to prioritize a plan that will make the building accessible for all students.